One of Latin America’s most celebrated journalists, whose work has toppled presidents and sparked criminal investigations into government wrongdoing, was recovering from chemotherapy when he received more bad news: A Peruvian prosecutor was investigating him for bribery.

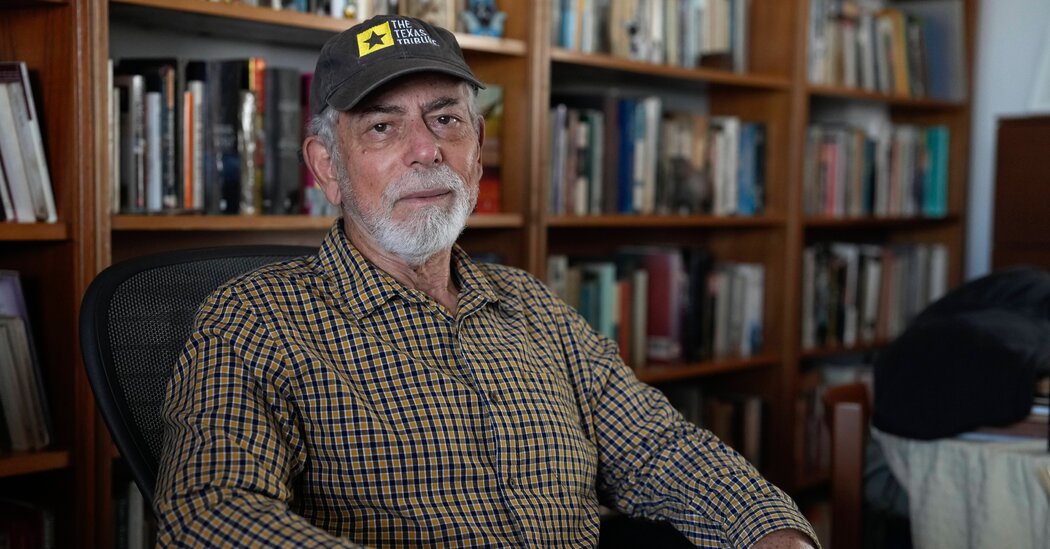

The journalist, Gustavo Gorriti, 76, is the editor-in-chief of an investigative news media organization in Peru and is no stranger to trouble.

He was abducted in the 1990s by a secret death squad that Peruvian investigators later determined was led by former President Alberto Fujimori, whose government Gorriti had reported for years on corruption and human rights abuses.

More recently, he helped uncover the massive bribery scandal known as Operation Car Wash, which led to the arrests and resignations of government officials across Latin America.

Now Mr. Gorriti himself faces a jail term.

Peru's attorney general accused him of taking bribes, claiming he provided favorable coverage in exchange for government leaks. Gorriti has denied the allegations.

Journalists and free-speech supporters said the charge was politically motivated and intended to punish Mr. Gorriti for past investigations.

The case against him is one of a series of attacks on independent news media in Peru and part of a broader wave of censorship of journalists in a growing number of Central and South American countries, according to press freedom groups.

“More and more politicians are smearing journalists and the media in their speeches. Politicians are using disinformation campaigns, abusive prosecutions and state propaganda to openly foster distrust of the press and encourage polarization,” said Reporters Without Borders.

In Peru, analysts say attacks on journalists reflect a wider democratic backsliding.

The conservative coalition in the legislature has sought to circumvent the legislative process and install allies in the country’s courts, electoral bodies and attorney general’s office to consolidate power.

Conservative lawmakers also passed legislation to make it more difficult to investigate, prosecute and punish corruption cases, and amended the constitution to increase the power of the legislature.

And they are increasingly using that power to hold journalists accountable.

Journalist Paola Ugaz faces multiple criminal investigations, including money laundering charges, for exposing years of child sex abuse and corruption at an influential religious organization in Peru.

Other journalists have been convicted of libel for reporting on politicians, religious organizations and sports officials.

International press freedom groups agree that Peru is becoming less friendly to journalists. Over the past two years, the country’s ranking in the press freedom index maintained by Reporters Without Borders has fallen sharply. It fell from 125 to 77, the largest drop in Latin America.

Freedom House, a human rights organization that assesses the levels of freedom in countries around the world, recently conducted a study that downgraded Peru's freedom rating from “free” to “partly free” last year.

The organization said The country has seen “Judicial independence has weakened,” and “high-profile corruption scandals have eroded public trust in the government, while deep divisions within a highly divided political class have repeatedly sparked political turmoil.”

Mr. Gorriti is editor-in-chief of IDL-Reporteros, a Peruvian investigative website known for exposing corruption among the powerful.

He began his Record The report uncovered the rise of the violent Shining Path rebel group in the 1980s and revealed ties to drug trafficking by a senior intelligence officer under Fujimori who, according to investigators, later ordered his kidnapping.

The kidnapping ultimately led to Mr. Fujimori being sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2009 on multiple charges.

Mr. Gorriti moved to Panama, where he exposed links between government officials and drug traffickers for a Panamanian newspaper.

His reporting has implicated four former Peruvian presidents, who held power between 2001 and 2020, in some form of wrongdoing. One of them was Alan García, Death When authorities arrived to arrest him, he shot himself in his home.

Gorriti said the bribery investigation was notable despite decades of what he called persecution.

“Under Fujimori, there was an imminent crisis of personal safety,” he said in an interview. But now, he said, current government officials “are turning the entire justice system into an additional tool for them. The situation is much more serious now than before.”

“It is shocking that they would take such a step against one of their most famous journalists,” said Artur Romeu, Latin American bureau chief for Reporters Without Borders.

After years of authoritarian rule under Mr Fujimori, Peru’s 2000 elections ushered in an era of thriving democracy, economic growth and free speech.

But in recent years, the economy has fallen into recession and trust in government has plummeted. Courts used to silence critics.

Mr. Gorriti and other journalists have also been harassed by right-wing groups that have demonstrated outside their offices and thrown feces at their homes. Right-wing television stations have often spread false information about independent journalists, accusing Mr. Gorriti of being a criminal mastermind.

As part of their investigation, prosecutors also asked Goriti to hand over the cellphone he used in his reporting and to reveal his sources, but he refused to do so.

Jonathan Castro, a political reporter and podcast editor, said the case against Gorriti makes other journalists’ jobs more difficult.

“Some sources are no longer providing information because they are afraid,” he said.

The government has filed defamation lawsuits against journalists in the past but is increasingly pursuing more serious criminal charges.

In an interview, Ugaz, a journalist accused of money laundering, said she had received death threats on social media and been verbally abused on the streets of the capital, Lima, because of a disinformation campaign against her, including false accusations that she had smuggled uranium and plutonium with the family of Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa.

“There’s no filter,” she said. “You think this is all so ridiculous and no one is going to believe it.”